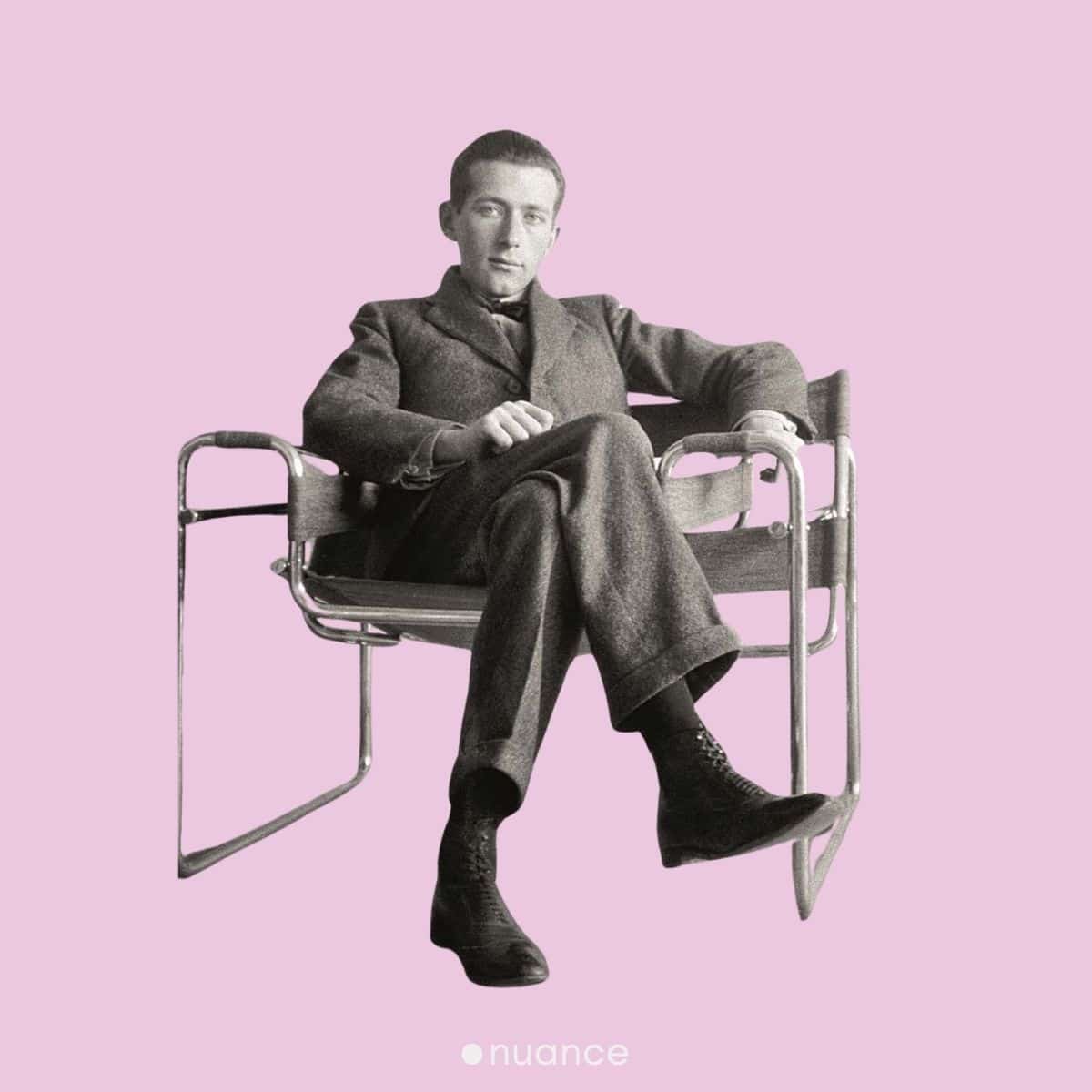

Marcel Breuer

The name that changed interior design with mid-century furniture icons.

Marcel Breuer pushed mid-century furniture forward. He mixed bold ideas with everyday function and nailed the look, too. Born a young artist in Hungary, he grew into a modernist heavyweight. His career captures the fresh energy that shook up design in the 1900s.

Structure is not just means to a solution. It is also a principle and a passion.

Marcel Breuer

Marcel Breuer

Pioneer of modernist design

Marcel Breuer (1902-1981) was an eminent architect and furniture designer who contributed his creativity to the modernist movement. His innovative approach in designing, with clean lines and functional forms, had made them a permanent imprint in architecture and furniture design. This article attempts to give a view into the life of Breuer, his most iconic work, and the legacy that he left behind.

Early life and education

Marcel Breuer was born in 1902 in Pécs. A southern Hungarian city layered with Roman ruins, Ottoman baths, Baroque churches, and tidy Neo-classical streets. His parents – well-off, cultured, Jewish – hoped their youngest would be a lawyer or doctor, but Marcel preferred wax sculptures and sketchbooks. Pécs looked historic and worldly, yet Breuer felt cut off. Serbia and the new Yugoslav state occupied the region after World War I. He later said he “knew nothing of modern art” growing up.

At eighteen he headed to Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts, chasing a bigger scene. It fizzled fast. He found the students and professors “blasés” and the young intellectual artists he encountered to be uninspired, despite their use of grand words.

In 1920, fresh out of secondary school, he tried Vienna’s Akademie der Bildenden Kunst. The romance fizzled fast. Professors and classmates struck him as blasé, their lofty talk masking a lack of real spark. After barely two months he quit, and took a drafting job with a local architect named Bolek.

The answer arrived in a brochure: the Bauhaus in Weimar promised to merge art, craft, and industry. He arrived, as he put it, a “true innocent”. The workshops, teachers like Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, and a tight circle of new friends flipped his focus from painting toward furniture, then architecture. Those Bauhaus years lit the fuse for everything that followed.

Bauhaus influence

At the Bauhaus, Marcel Breuer found the people who would shape him for life. Walter Gropius, the school’s founding director, took Breuer under his wing. Gropius preached that architecture should fuse every art and craft. He nudged the young Hungarian away from painting and into the carpentry shop – there was no architecture department yet. Breuer helped out in the Gropius & Meyer office, picking up real-world lessons on projects like the timber-rich Sommerfeld House and the experimental Haus am Horn.

Next came Johannes Itten, head of the infamous preliminary course. Itten made students hunt contrasts – light versus dark, rough versus smooth – and build collages from scraps. Breuer later teased him as a “magician”, but those early material mash-ups clearly stuck.

The deepest impact came from Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. Breuer called Klee the “sage of the Bauhaus”. Years later he honored Kandinsky by renaming the B-3 tubular armchair the “Wassily” chair. Both artists taught that every shape lives in tension with its opposite. They saw duality as the engine of the universe.

Klee called it the “duality of a unity”. Kandinsky wrote whole books – Point and Line to Plane – about how a figure and its background pull on each other. Breuer absorbed that idea wholesale. It became his own mantra of “Sun and Shadow”, the belief that design should leave opposing forces visible and alive.

Core philosophy

“Sun and shadow”

Marcel Breuer designed for tension. He called his guiding idea “Sun and Shadow”, a Spanish proverb that reminds us life always holds two extremes at once. Instead of blending those extremes, Breuer set them side by side. Light with heavy, glass with stone, hand-woven cane with chrome steel – so each could shine in full strength.

He learned this mindset at the Bauhaus under Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, who treated every form as a tug-of-war between forces. Surrealism then nudged him to place “wrong” things together on purpose. Creating that slightly unsettling spark you feel when chunky concrete hovers over a thin glass wall.

Early brushes with De Stijl sharpened his love for crisp lines and primary shapes. While road trips through Mediterranean villages showed him the quiet power of rough stone and timber. Partnering later with engineer Pier Luigi Nervi, Breuer bent concrete into swooping hyperbolic shells. Bold shapes that looked structural even when they were half sculpture.

He stayed loyal to Modernism’s core. Clarity of form, honest materials, factory precision. But he never chased a smooth, polite finish. Breuer wanted friction: machine against craft, experiment against comfort. That tension is why his work still feels alive today.

Iconic furniture designs

Marcel Breuer’s furniture design was a crucial phase in his career. Serving as an early testing ground for the philosophical and artistic influences that would later define his architectural approach.

Breuer’s furniture story starts with the “African” chair (co-designed with textile ace Gunta Stölz). It’s pure early-Bauhaus: bold, handmade, a mash-up of art and craft that felt more expressionist than machine-age.

Then Theo van Doesburg rolled through Weimar with his De Stijl pep talks. Breuer soaked it up. His Wood Slat Chair (1922-24) breaks the seat down to skinny, straight lines. Think Gerrit Rietveld, but kinder to your backside. Breuer slipped in fabric webbing so you could actually sit for a while. Practicality 1, purism 0.

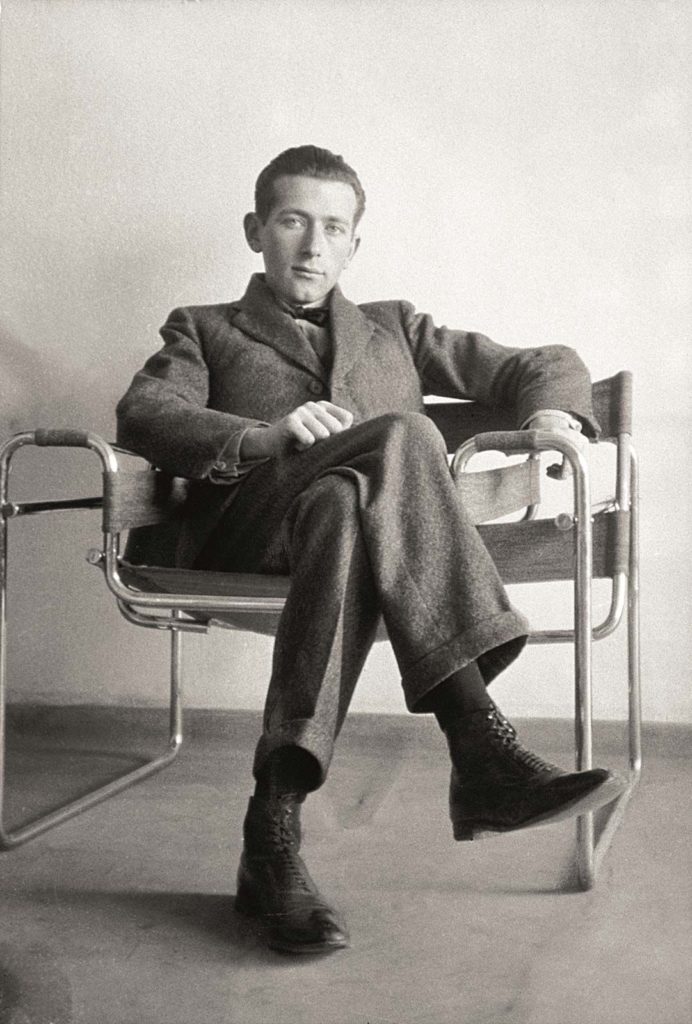

Wassily Chair (Model B3)

Marcel Breuer hit his stride in 1925 with the B-3 chair, later nicknamed the Wassily. He was still at the Bauhaus in Dessau, playing with modernist ideas and new materials. One day he bought a bicycle, a friend joked the steel tubes bent “like macaroni”. Lightbulb moment. Breuer swapped wood for shiny, lightweight chrome tubing and stretched canvas for comfort.

The result looked nothing like the plump armchairs of the time. Thin lines outlined an invisible cube, turning empty space into the main event. It was factory-ready, easy to ship, and dead simple to assemble – pure Bauhaus modernism.

The chair’s success pushed Breuer to design a whole family of bent-steel pieces over the next decade. Critics later focused on his buildings, but this early furniture work set the stage. It taught him how materials, structure, and volume could dance together – lessons he carried straight into his architecture.

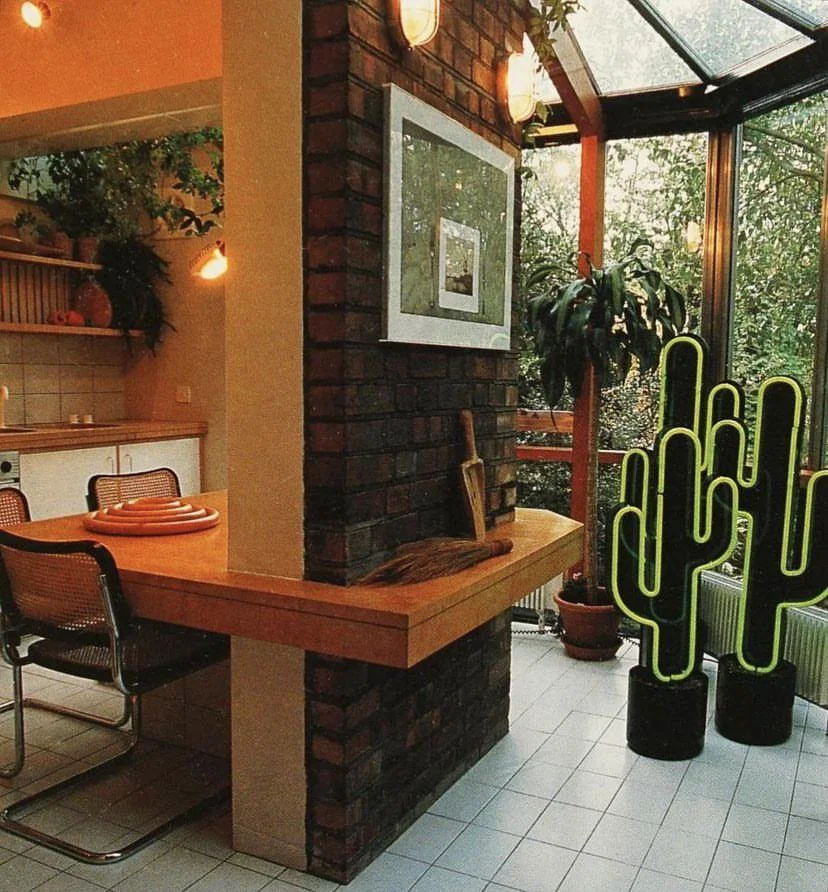

The Cesca Chair

Another game-changer is a design that Breuer applied in 1928, called the Cesca Chair. Back then it was simply B32. He bent a single tube of chrome steel into a clean cantilever that floats the seat in mid-air.

For the seat and back, he kept it old-school: hand-woven cane, framed in bent wood, then screwed onto the metal. No weaving the cane around the frame, like Mies did on his S533R. Thonet had long attached seats this way on its bent-wood chairs, so Breuer’s method also nodded to manufacturing tradition.

Breuer wanted the parts to stay separate so the contrast pops – chrome versus wood, machine versus hand, modern versus traditional. Bonus: if the cane ever sags, you just swap the panel.

Lightweight, space-defining, and cheap to make, the Cesca ticked every late-’20s Modernist box-machine production, clear volume, elemental form. Breuer called this clash a “unity of opposites”. He refused to blend materials. He staged them side by side, the same way he would later stage stone against concrete in his buildings.

Breuer’s Architecture

Marcel Breuer enjoyed big wins and sharp jabs all at once. Over forty years, his studio turned out nearly 150 buildings across Europe and the Americas – corporate HQs for IBM and Armstrong, bold post-Vatican-II churches, college campuses, and the much-praised Whitney Museum in New York.

Awards poured in: the AIA Gold Medal, Italy’s Compasso d’Oro, France’s Grand Médaille d’Or. MoMA even asked him to build a model house in its garden, and Harvard hired him to teach a generation of Modernists. On paper, he stood shoulder to shoulder with Gropius and Mies.

Yet critics never let him forget he wasn’t quite one of the “masters”. By the mid-1960s, voices like Vincent Scully and William H. Jordy said his big projects felt too graphic, too detail-obsessed, lacking the monumental weight they expected from large buildings. Jordy went so far as to call St. John’s Abbey Church “furniture-like”.

That “awkwardness”, those abrupt clashes of scale and material, were the point. Breuer’s guiding mantra – “Sun and Shadow”, the unity of opposites – asked contrasting elements to sit together, undiluted, no tidy blend. The UNESCO Headquarters, the Atlanta Central Library: critics saw disjointed parts, Breuer saw honest tension.

Still, when people list his greatest hits, they start with furniture – the Wassily and Cesca chairs often eclipse his architecture. Breuer reached the top tier in clients, fees, and trophies, but his refusal to smooth over contrasts left the jury forever split on his buildings.

Whitney Museum of American Art

The former Whitney Museum of American Art on Madison Avenue stands as Marcel Breuer’s best-known building and one of his most celebrated commissions. Critics hailed it on opening day as a benchmark for modern museum design, and the job gave Breuer’s New York office more public visibility than even his pioneering Midwestern churches.

Breuer saw the museum as an “independent, self-reliant unit” that had to hold its own amid Manhattan’s “dynamic jungle”. He shaped it as a solid gray-granite block that steps outward like an upside-down staircase as it rises. What one critic nicknamed as a “Kunstbunker” (an art bunker). Deep reveals separate the granite shell from adjacent buildings so the museum reads as a freestanding on the corner, emphasizing its identity as a “unit, an element, a nucleus”.

Most daylight is shut out, only a handful of trapezoidal, hooded windows – Breuer called them the building’s “eyes” – pierce the stone. Freed from strict lighting duties, these openings could be placed “in a free and less inhibited fashion”, acting as sculptural contrasts and echoing his “Sun and Shadow” focus on deliberate opposites.

At street level, the mass pulls back to create a sunken “moat”. A concrete bridge, lightly touching the glass lobby wall, spans this gap. Visually underscoring the fragile link between bustling city life and the quieter realm of art inside. The result, in Architectural historian Barry Bergdoll’s words, is one of Breuer’s signature feats of “heavy lightness”. A massive granite volume floating above a glass base.

With the Whitney, Breuer showed how a modern building could mediate between the tight nineteenth-century grid and Modernism’s utopian future. Opaque, textured, and protective, its facade announces another world even as the glass ground floor lets passers-by glimpse it. The ideas honed here – mass versus void, weight versus suspension, city versus sanctuary – set the stage for later urban landmarks such as Atlanta’s Central Library.

Saint Johns Abbey Church

The Benedictines wanted a church that matched the spirit of the new liturgy. That meant everyone – clergy and laypeople – close to the altar, sharing one space instead of watching from afar. Breuer answered with modern tools, not Gothic copies: raw concrete, bold forms, stripped-down structure.

A single “spiritual axis” guides you from the bell banner outside, through the baptistery, straight to the high altar and the abbot’s throne. Every seat gets a clear view. Nothing is hidden: the concrete frame and the marks of construction double as ornament.

Modern artworks – abstract yet devotional – add color and meaning that today’s worshippers can read. The monks pitched in, honoring their tradition of manual labor and community. In the end, the building functions like a living liturgical machine, perfectly tuned to post-Vatican-II worship and still unmistakably Benedictine.

How Breuer shaped Post-War design and architecture

Teaching the next wave of Modernists

Breuer’s studio and classrooms turned out future stars. I.M. Pei, Harry Seidler, Edward Larabee Barnes, John Johansen, Richard Meier, and Beverly Lorraine Greene, the first licensed African-American woman architect, all passed through his circle as students, employees, or close colleagues.

Spreading a “Sun and Shadow” mindset

His guiding idea, “Sun and Shadow”, asked designers to set clear opposites – light and heavy, glass and concrete – side by side without blending them. Rooted in Bauhaus lessons from Klee and Kandinsky, this stance offered a different route through post-war Modernism, one critics sometimes mistook for poor large-scale composition.

Working with additive, kit-like plans

Breuer’s office often chose a basic house type and then clipped on extra parts to suit site or program. The result was a loose “kit” of mostly self-contained elements whose deliberate clashes of meaning gave the buildings the “strangeness and ambiguity” reviewers noted.

Pushing concrete toward mass and sculpture

After teaming with Pier Luigi Nervi at UNESCO, Breuer chased solidity. Precast panels, deep folds, and chunky pilotis – first at IBM La Gaude – let him fuse structure, surface, and pure sculptural impact. Prisms, antiprisms, and ruled surfaces carried weight even when they weren’t strictly structural.

Perfecting “heavy lightness”

Barry Bergdoll’s phrase captures Breuer’s trick of floating big stone or concrete volumes above glassy ground floors – St. John’s Abbey Church and the Whitney in New York are textbook examples – creating a Surreal jolt where mass seems to hover.

Recasting the building–city relationship

In projects like the Whitney Museum and Atlanta Central Library, Breuer treated the city as a backdrop and the building as an independent, almost mute container. Opaque, faceted facades with just a few strategic windows hold an “otherworldliness”. Separating art or learning from the surrounding urban jungle while still tapping the street’s energy.

This post may contain affiliate links, meaning I earn a small commission if you purchase through these links, at no additional cost to you. I only recommend products I genuinely love and think you’ll love too. Your support helps keep this blog running – thank you!

Sources

John Poros – Marcel Breuer: Shaping Architecture in the Post-War Era (Routledge Research in Architecture)

Marcel Breuer – Sun and Shadow: The Philosophy of an Architect

Victoria M. Young – Saint John’s Abbey Church: Marcel Breuer and the Creation of a Modern Sacred Space